By: Amber Perry and Madeline Laguaite

Wall Street Journal reporter John Carreyrou was sitting on the subway in 2014 when he read a New Yorker profile about Elizabeth Holmes. The story explained how Holmes’ company, Theranos, had created a breakthrough product that only needed a pin-prick of blood to diagnose an array of medical conditions.

Reports about this “too-good-to-be-true” blood-testing device prompted Carreyrou to do a second take. His curiosity would ultimately lead to what he describes as the “biggest and most compelling” story he’s ever written. In a series of articles in the Wall Street Journal in 2015, he exposed concerns about the effectiveness of Theranos’ technology and questioned if the company had the science to back its claims.

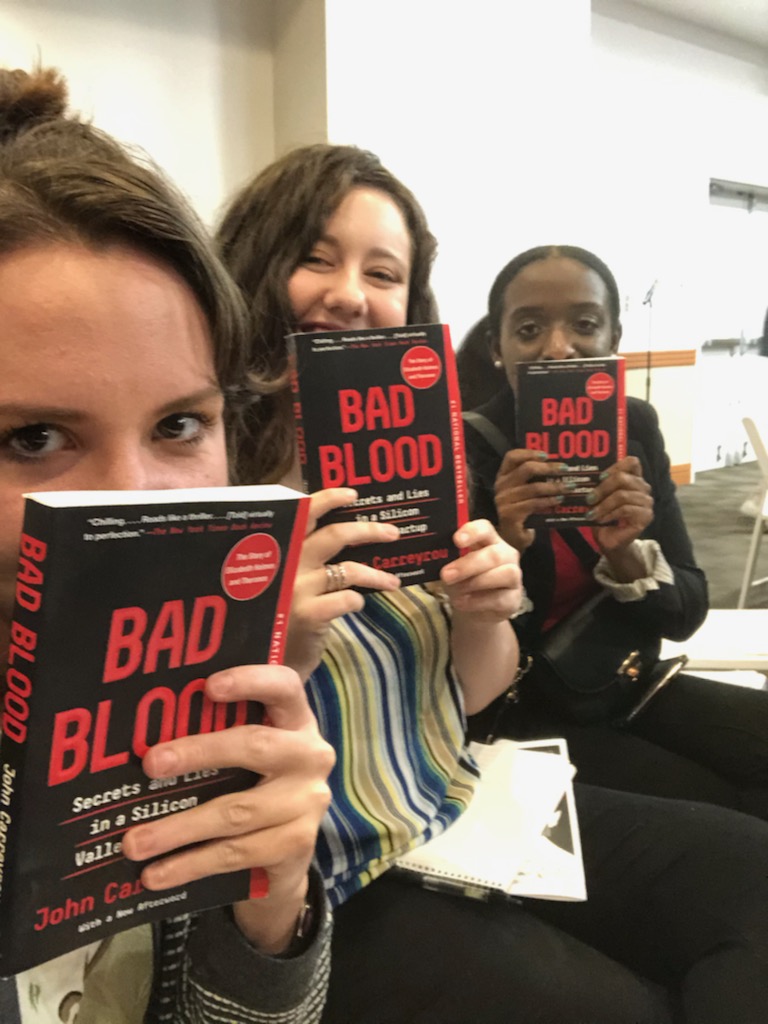

“I’m the type of reporter who follows ledes organically,” Carreyrou explained last month in a conversation with Emmy Award-winning journalist Melissa Long. During the event at the Marcus Jewish Community Center in Atlanta, he spoke about his bestseller — Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup — a book that resulted from his dogged reporting.

An archeological dig

Until Carreyrou’s exposé, news reports tended to either uplift Holmes for being the “youngest woman to become a self-made billionaire,” or laud Theranos as a “revolutionary blood diagnostics company.” In his conversation with Long, Carreyrou said “Bad Blood” (released in 2017) was an archeological exploration of Holmes’ world. It included conversations with colleagues who used to work for her Palo Alto-based startup, former classmates and professors, family members, psychologists, and others.

A tip received weeks after he read the New Yorker profile prompted him to follow his hunch, Carreyrou told the audience. Dr. Adam Clapper, a pathologist (a medical doctor responsible for performing and deciphering lab tests) and author of a now-defunct blog called Pathology Blawg, created a post that evoked responses from a band of Theranos skeptics. That blog eventually led to a primary source, a person with direct knowledge of the situation.

The original news story explained how the technology that Theranos used to diagnose conditions like vitamin D deficiency and prostate cancer didn’t generate consistent results. Potassium level readings, at times, rendered results so high “that patients would have to be dead for the results to be correct,” according to a former employee quoted in Carreyrou’s Wall Street Journal story.

“Is this a psychopath?”

Carreyrou told the audience in Atlanta that the book included sources from Holmes’s past and present, examined the dynamic of her relationships and tried to understand who she was as a person.

He learned for example, that Holmes was 9 years old when she professed her goal of becoming “hugely rich” at a family gathering. That sometimes she would get so angry during a game of Monopoly that she’d throw the board. And that she had an “almost cartoonish” fascination with Apple Computer co-founder, Steve Jobs. So much so, Carreyrou said, that after Jobs’ death, Holmes wanted to fly an Apple flag at half-mast to honor him.

He was “a looming figure of her psyche,” Carreyrou said.

“Is this a psychopath?” Long asked about Holmes.

A psychologist in Manhattan described her as a “malignant narcissist,” Carreyrou responded.

As aspiring journalists, it was impressive to see how Carreyrou was able to create a web of sources and build the story into what it is today. He spent around three years reporting and writing about both Holmes and Theranos. He was able to answer upwards of 20 audience questions with precision, an attribute of a solid investigative journalist.